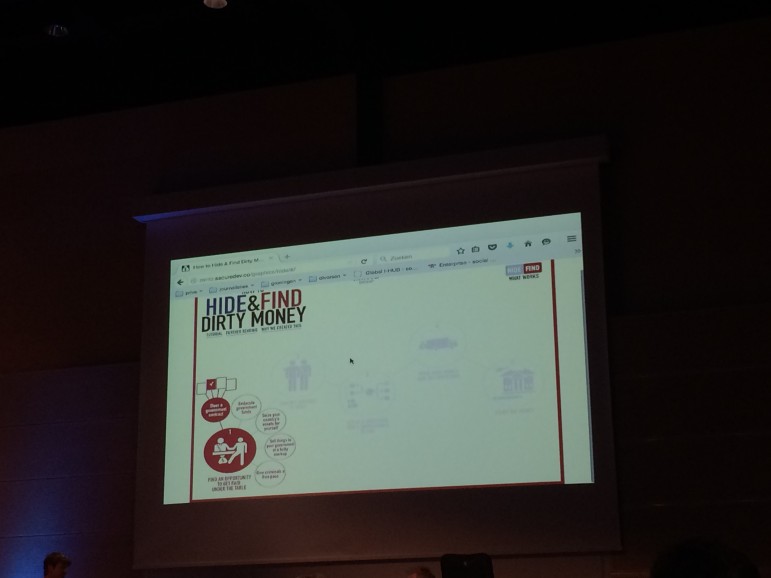

Jim Mintz presents his interactive guide: Hide & Find Dirty Money.

“The skill of digging into complex wrongdoing is required for both my day job and my evening job,” said Jim Mintz, founder of the Mintz Group, of his days as a private investigator and his nights teaching investigative reporting at Columbia University.

Investigators in all sectors have traditional methods and techniques for digging up information to track and document wrongdoing. At the panel: How other investigators do it, Margo Smit moderated a discussion around commonalities between industries and techniques transferable to journalism.

In his interactive guide: Hide & Find Dirty Money, Mintz shared five ways to “think like a public official with a pay off coming his way.” An exercise he has successfully used to identify important clues, people and places on the path of uncovering dirty money.

- Find a way to get paid under the table like steering a government contract, embezzling government funds, seizing your country’s assets yourself, or giving criminals a free pass.

- Identify someone to trust, like a family member, friend or lawyer, because you probably won’t hide the money yourself

- Set up a structure that is untraceable like an offshore bank account and fictional account holders.

- Move your money into the structure.

- Enjoy the money by shopping, buying luxurious vehicles and living like a king.

Mintz tells his students they can learn a thing or two from investigators in other sectors—like accounting firms or law enforcement agencies—where investigative techniques are being employed.

“We want the same goal,” said former FBI agent Joe Davidson, who spoke about the similarities between investigative journalists and officers of the law. “We’re just trying to put the bad guys in jail and we want the truth to come out.”

Law enforcement officials and journalists, he said, will initially view each other as adversaries, but a good relationship between the two could prove fruitful for both.

For journalists looking to approach a law enforcement agent, Davidson suggests you should:

- Be honest both about your intentions and in your reporting process.

- Every FBI office has a media representative get access to the right person. If you call them and describe the particular case you want to discuss, at the very least you’ll score a meeting with the supervisor.

- When you meet with the supervisor or case agent, sell yourself. You have only one chance to sell yourself as professional, smart and non-sensational journalist. If you can, share a little information about the case with the law enforcement agent, it could go a long way.

Even with the ability to wiretap or pay for information, luxuries that journalists do not have, Davidson said 95% of his cases were a result of a “real body source.”

“Genuine secrets, even in the age of big data, are still in the heads of fellow human beings,” Davidson remarked. “And we have to be really, really good at getting them to give up those secrets.”

Abby Ellis reports on this event as part of the IACC Young Journalists Initiative, a network reporting on corruption around the globe.

Abby Ellis reports on this event as part of the IACC Young Journalists Initiative, a network reporting on corruption around the globe.